Creating A Visual Language For Queer, Brown Femininity — On Its Own Terms

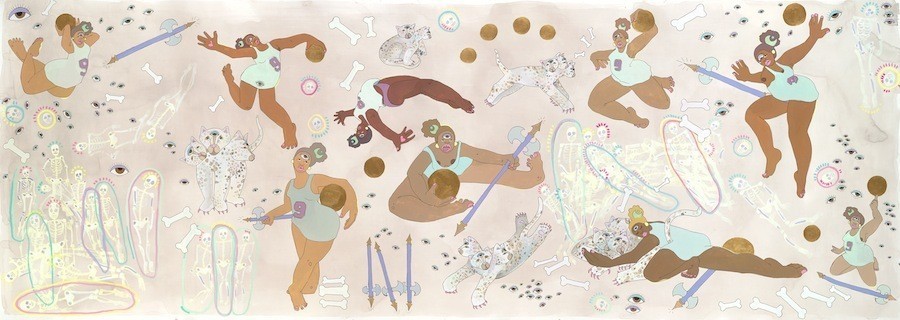

Instructions for a Home Team

“The cyborg is a kind of disassembled and reassembled, postmodern collective and personal self,” Donna J. Haraway writes in Simians, Cyborgs And Women: The Reinvention Of Nature. “This is the self feminists must code.” Haraway uses the metaphor of a cyborg — part human, part machine — as a call to action for feminists to break down the existing structures that limit, oppress and marginalize. Structures that have rooted themselves more deeply than many of us realize.

Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski, an artist who’s attempted to paint in a language that sits outside the Euro-centric history we’re used to, is familiar with how deep-seated traditions can become. In her work, Moleski began by painting women — brown, queer, femme — and nothing else, providing visibility to a subject so long excluded by the dominant art narrative.

She soon realized, however, that although her subject matter had broken free of convention, her tools were still entangled in canon, in traditions of proportion, scale, and perspective. That’s when the crux of Moleski’s project, to truly work outside the systems established decisively not for her, took root.

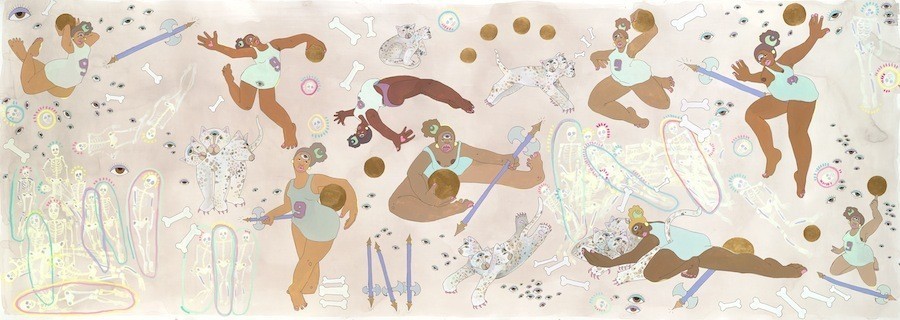

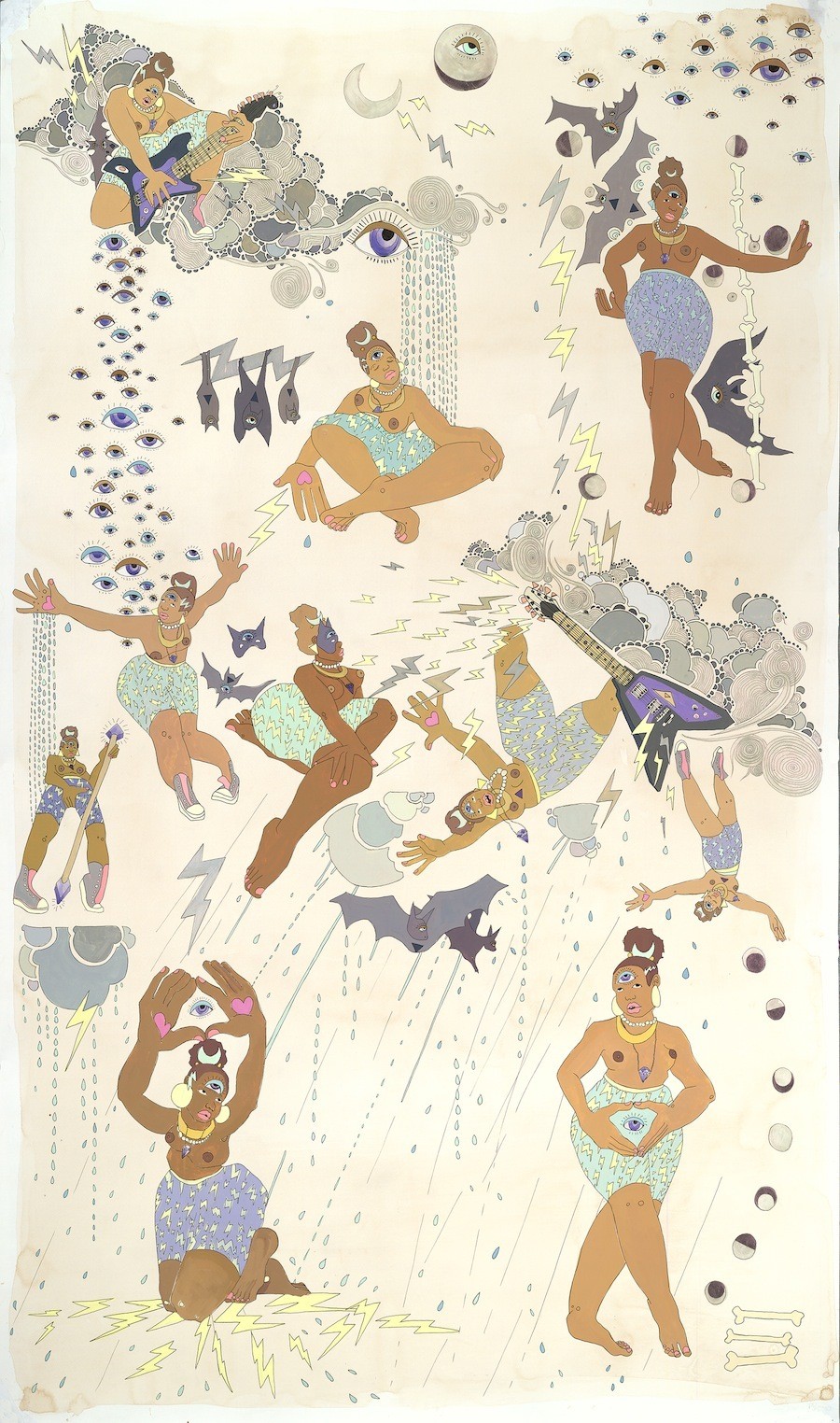

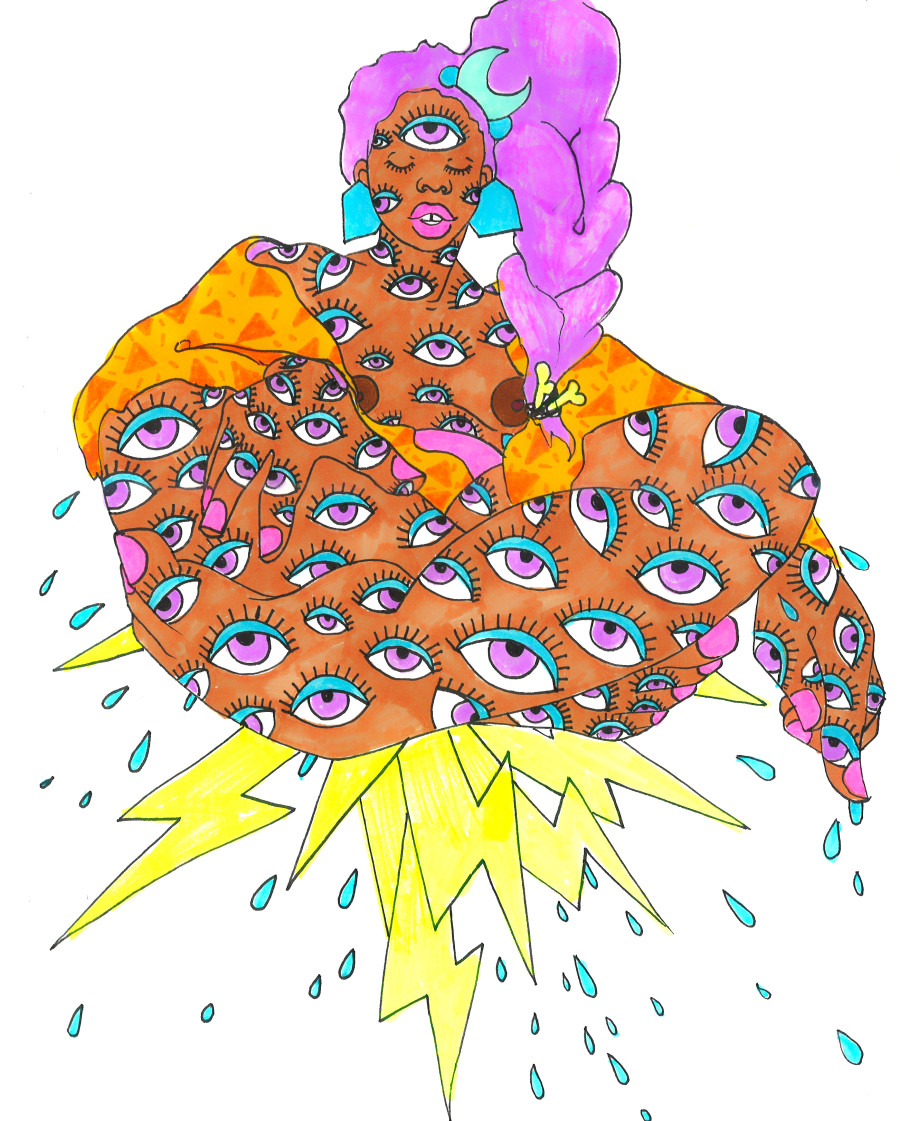

Inspired by artists including Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas and Saya Woolfalk, Moleski created a visual lexicon somewhere between the ancient past and the imaginary future. Sprinkling in influences ranging from “Battlestar Galactica” to Judith Butler, Greco-Roman mythology to the cuteness of caterpillars, Moleski built a visual utopia filled with curvaceous bodies, dolled-up fashion, flattened patterns and lots and lots of eyeballs.

Moleski’s sci-fi inflected goddesses are currently on view as part of an exhibition titled “Vision Quest” at New York’s Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA). We reached out to Moleski to learn more about her life and work.

Instructions for a Storm

Let’s start at the beginning. Where did you grow up?

I grew up moving around all my life. I grew up all over the East Coast, down South and Midwest. We moved at least once a year, so by the time I was 14, I counted, and we had moved about 16 times. So in terms of having a geographic place where I grew up, I don’t really have that, it’s more of those parts of the country.

Do you remember first becoming interested in art?

I was fortunate enough to grow up in a house where my mom was really aware that I loved to draw, that I could entertain myself for hours that way, and she was really supportive of that. When I was in grade school, she got me this book called Life Doesn’t Frighten Me, and the text was a poem by Maya Angelou. And the poem was pieced together with different Basquiat paintings. The words and the paintings, the way they came together — that’s something I’ll always remember as part of my artist roots.

Also, my father was incarcerated on and off my whole life, in different states than I lived. So our main mode of communication was by letter. He’d hire artists that he was locked up with to create portraits of us. I loved Garfield, I was a huge fan, and he had his cellmates draw Garfield cartoons for me. I remember the images more than I remember the verbal correspondence. It was this connection that was created between us, even through that separation. So, in that way, I was really nurtured by visual art and images growing up.

Do you recall initially realizing the homogeneity of the Western canon of art history? What was your reaction?

You know, it’s almost like elevator music when I think about that. It’s like background noise in that, I did, like all of us have, see it all. But it never stuck with me, it was never the thing that really grabbed me or caught my attention. And it wasn’t anything necessarily I could relate to.

I went to this arts camp when I was a little older and they would take us on trips to the art museums in the area and that was the first time that I really saw museum art. That was the first time I interacted with those kinds of works and that kind of canon. And then later when I went to art school I was like, “whoa!” I realized then that when they’re teaching art history, that pretty much means European art history.

Bone Oracle

Did this realization impact your practice?

I’m really thankful for that education and how rigorous it was. However, one thing I was really not ready for was how Eurocentric the curriculum was. On the one hand it’s important to understand it, seeing as it’s a part of the history of the art world, and on the other hand it was so exhausting. It just made me think: What am I even doing here?

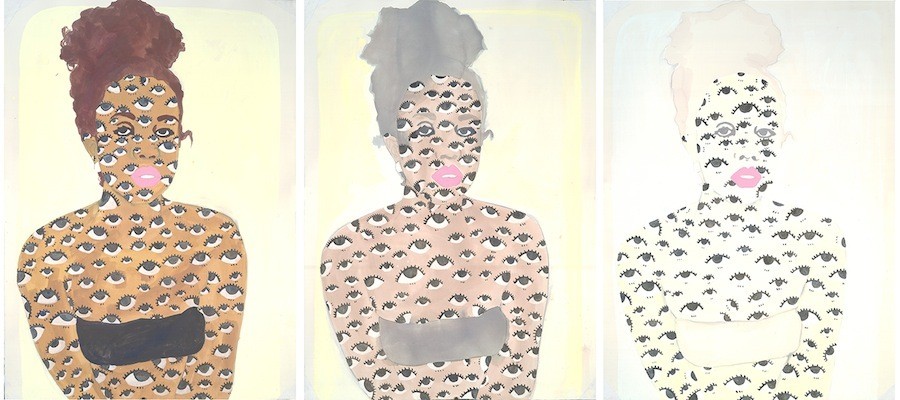

It wasn’t just art history, but it was also playing into the politics of aesthetics, what could be discussed rigorously and critiqued. I just got this point where I decided I was only going to draw queer, femme, brown and black people. That’s all it’s gonna be. I’ve kind of evolved past that at this point but it was a really clear decision. Being so hungry for it and deciding I was going to create it.

Is this related to what you refer to in your statement as the future femme myth? Can you expand on what exactly that means?

Yes, that exploration is something that I’m going to be excited to think about for a long time. I was creating these portraits in a series called “Femme Gold” and I was rendering queer femmes of color and trying to expand what that could look like. I was asking — how do you represent the aesthetics of queer femininity, without placing the body in relationship to someone else. What is the aesthetic of queer femininity when its not dependent on who’s gazing?

I was thinking about that and I had this personal breakthrough that I had made this decision to move away from the European canon and art history and yet I was still using the same rules of proportion and scale and portraiture. Even though I was trying to use different symbols, the vehicle I was using was based and rooted in classical European tradition.

Then I thought to myself, okay, if not that, where will I look for guidance? And I started becoming inspired by all these pre-Columbian artworks and looking a lot at alchemical illustrations that used visual language as a text to be read. I’m super inspired by Saya Woolfalk as a contemporary artist who is calling upon the aesthetics of ancient and folk art.

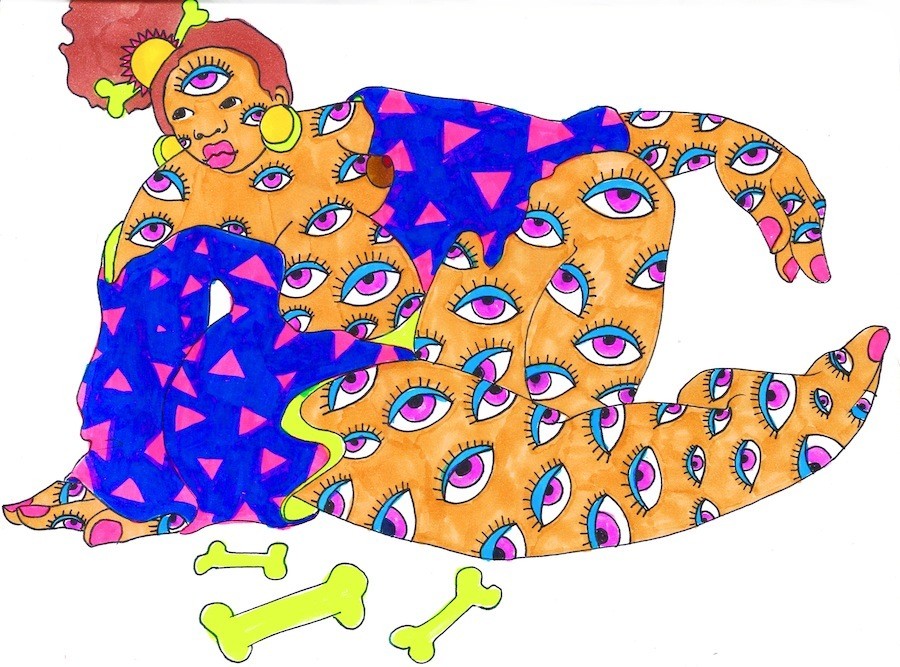

Sooth Sayer

And how did the futuristic aspect come into play?

I’m a super big sci-fi nerd and I started thinking about the future. There has been an upsurge in post-apocalyptic, sci-fi and fantasy narratives, and I started to experience this hunger for a different narrative, a different story being told.

There’s this idea within that world of future myths that the future equals more masculine, more tech-focused. It shows up in the narratives dealing with outer space versus Earth — we’re leaving the world that we messed up behind, and who are we taking with us? How is that future being portrayed? I was looking at something like “Star Trek,” which is pretty diverse for when it was made, and then looking at something like “Battlestar Galactica,” which is like this huge decline in representations of diversity of the human race in the future. I started getting interested in that combination. What is queer femme aesthetic? And how to we begin to visualize ourselves as marginalized people in the future, calling upon ancient, present and future imaginings?

One of the most pronounced features of your work are the multiplicity of eyes that surround many of your bodies. What prompted you there?

It’s a symbol that is appealing to me because it’s pretty global in terms of all the different representations of spiritual texts and ancient art texts across the board.

Also, I’m curious about the aesthetics of holiness and eyes have this divine omnipresent awareness to them, something that’s contained all around us and within us. Eyes are symbols of protection, symbols of sovereignty. I place them everywhere to show that they’re totally accessible.

Call Back Your Magics

Call Back Your Magics

The women you depict are powerful, and yet don’t don any of the markers we traditionally associate with strength or authority. How did you go about creating your own system of visual power?

Something I’m interested in is thinking about the feminine as a presentation or a play or a creative force in the world. I, personally, have used hair and makeup and clothes as armor. I feel like our culture diminishes women and those choices are considered unintelligent. Like, “Oh, you wear too much makeup.” Or, “Why are you wearing heels?”

In this way, it’s a tactic of people trying to bring the feminine down, implying that those choices aren’t intelligent and aren’t informed. And I’m thinking about the ways that they really are — they really are intelligent about how we fit in the world, especially as queer femmes.

I also am interested in cuteness as a sense of armor. Looking at that in caterpillars and butterflies and all of these small creatures that have made themselves appear a certain way to be protected. How do we make ourselves seem larger than life? Cuteness and femininity can be a source of protection and a source of fierceness.

Weave (for Swallow)

Can you describe the process of naming your works?

It started when I was was looking at a lot of ancient works and pre-Colombian art. Let me just say: I am not a historian, I am not a scientist. I do not know anything about the extensiveness and rigor of the processes of uncovering these histories. But from the outside looking in, as an artist, there was something really humorous to me about the authority involved in these histories. Who is coming up with this shit? Who is saying this is how it was?

I became curious about this voice of authority, who is telling the history, whose history is being canonized as myth and whose history is being categorized as truth. I started to think about using authority as a medium to play with. To use language as my own sense of authority and sovereignty and dominion over whatever it is I’m making. I think having a mixture of play and power behind the intentionality of language is important in my work.

Your statement mentions the influence of Donna Haraway’s The Cyborg Manifesto on your work. Can you describe what, specifically, inspired you about the text?

To be totally honest, The Cyborg Manifesto was something I read in school. I don’t know how anyone would read it outside of school because it’s so academic. Reading it, I remember feeling this frustration around protection of information. This cloaking of information in really academic language.

But I gave it some more time, and there were pieces that really spoke to me, about creation myths and disassembling the systems of history, disassembling systems of language and power and rearranging them. It also spoke to me in how I think queerness functions as a healing force in the world — breaking down different structures and systems and rearranging them in a way that is catering to the full expression of someone’s soul. It’s about deconstructing what we’ve inherited as our origins. And being able to piece them back together in a way that serves the whole expression of who we are as human beings.

Documentation of a Ghostin

Moleski’s work is on view alongside that of Sheena Rose in “Vision Quest,” which runs until May 31, 2015 at MoCADA in Brooklyn, New York.

.articleBody div.feature-section, .entry div.feature-section{width:55%;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;} .articleBody span.feature-dropcap, .entry span.feature-dropcap{float:left;font-size:72px;line-height:59px;padding-top:4px;padding-right:8px;padding-left:3px;} div.feature-caption{font-size:90%;margin-top:0px;}

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Source: Huffington Post Women