Women's Colleges Are Admitting Trans And Gender-Fluid Applicants. Now What?

OAKLAND, Calif. — Ten years ago, Erin Armstrong was forced to drop out of college in Utah because her parents refused to pay her tuition when she came out as transgender. She sold nearly everything she owned, packed the remainder of her belongings into three suitcases and flew from her small hometown on a one-way ticket to New York City.

“That was a hot mess,” she said of her transition, in an interview with The Huffington Post at Mills College in Oakland, California. “People take for granted that they’re socialized one way for their whole life, and I wasn’t socialized as a girl, so I had a lot of learning to do.”

A woman she had been on one date with agreed to host her once she landed in the Big Apple — “I did the typical lesbian thing and moved in on the second date” — and she found a job working at a queer and trans-friendly costume store during the Halloween rush.

After three years at the shop, Armstrong coordinated a program to provide safe rides for New Yorkers looking for alternate forms of transportation. When she moved to San Francisco years later, she ran an HIV testing and prevention program for the country’s largest drop-in center for transgender people, including the city’s first HIV testing program specifically targeting transgender women of color. She was inspired to return to school and complete her bachelor’s degree when indiscriminate federal spending cuts hit her nonprofit organization, which received funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

She stumbled upon representatives for Mills, a women’s college in Oakland, advertising at the nearby Berkeley City College, where she was taking classes. Armstrong had heard about other women’s colleges, like Smith, rejecting transgender women applicants, so she approached with some trepidation. (Her wife is a Smith alumna and has advocated for the school to broaden its admissions policy. Smith just announced that it will admit transgender women this fall.) She had thought the possibility of attending a women’s college was out of reach.

“I walked up to them and said, ‘Hey, funny question, do you allow transgender women to come?'”

The Mills officials told her they admitted transgender and non-binary applicants on a case-by-case basis. She successfully transferred and began taking classes in September of last year.

*****

As a snowballing number of women’s colleges are publicizing new admissions policies for transgender and non-binary students, students are cautioning that these policies aren’t necessarily an inclusive panacea. The guidelines are a start, to be sure, but there’s more to fostering welcoming environments than announcing such applicants are welcome.

How women’s colleges treat their students who aren’t cisgender — those who don’t identity with the sex assigned to them at birth — matters because of how the world outside these relatively progressive institutions approaches transgender and non-binary people. Across the country, trans and non-binary individuals face greater threats of violence, discrimination in employment and housing, and difficulties accessing health care. In many states, Republican-controlled state legislatures are even trying to dictate where they’re allowed to urinate. Before going out into a world where acceptance is harder to come by, advocates say, students are entitled to feel safe for (at least) four years. Moreover, advocates hope the conversation about women’s colleges might raise awareness about the challenges trans and non-binary people face.

Armstrong, who was admitted to Mills before its first-in-the-nation policy was announced, said the school hasn’t necessarily been tested yet with a student who isn’t always accurately identified by others.

“I’m hoping I see, this coming year, more and more people who are coming to Mills just out of high school who are trans, people who are just barely starting their transition,” she said. “I’m over 10 years into it; it’s been one-third of my life, so it’s nothing new to me. I want to see how the school reacts when someone is just barely coming out: What does that look like? How are they able to support them through access to health care? How are they able to navigate restroom issues? What if there’s a student who doesn’t necessarily pass who is here as an undergrad? Is the school going to react differently?”

Critics of these admissions policies — women’s college alumni writing for major media publications among them — have argued the activism on behalf of transgender inclusion threatens to erase the schools’ women-empowering legacies and traditions. But it is the colleges’ very histories, supporters of the policies say, that make the argument for inclusion all the more compelling.

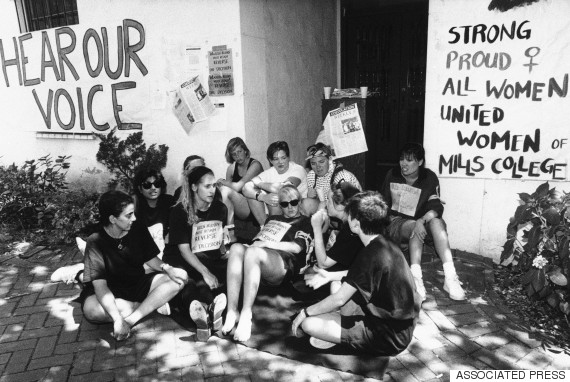

But it’s not like Mills hasn’t change its rules about sex and gender before. In 1990, the school’s board of trustees implemented a policy to admit undergraduate male students (the graduate school is co-ed) to bring in more revenue and improve its financial prospects. Mills women responded with protests, barricades and strikes, leading to a reversal of the decision.

Founded in 1852 as the Young Ladies’ Seminary, Mills is the oldest women’s college west of the Rocky Mountains, and even older than Stanford University and the University of California system. The purpose of the school was relatively new and progressive when it was founded: Miners, farmers and merchants wanted their daughters to receive an education without having to be taught elsewhere. Colleges for women flourished as the most elite universities, like Harvard and Yale, remained single-sex. The number of women’s colleges reached a peak of about 300 in the 1960s, but now there are only about 50, as liberal arts colleges with smaller endowments face tough financial environments.

“Women’s colleges were formed at a time when the education of women was a radical act, but it was premised on a particular notion of gender oppression, gender status and equality, which it still is about,” Professor Piya Chatterjee, the chair of Scripps’ Feminist, Gender and Sexuality Studies department, told HuffPost. “So, if it was premised on that kind of logic, how could we then turn around and police a gender minority? To include trans people is to recognize gender oppression. It goes to the very nub of why one would feel a women’s college should exist and is still important.”

Students of Mills College in Oakland, California, blockade access to a building on campus on May 4, 1990. The women plan to continue the blockades throughout the weekend. All campus facilities were closed as students protested on Thursday’s decision by the board of trustees to admit undergraduate men to the women’s school. (AP Photo/Kim Gerbich)

As Armstrong immediately found out when she arrived at Mills, she wasn’t able to blend in just like any other woman. Though she was already accustomed to a certain amount of visibility as a YouTube celebrity — videos she posts detailing her experiences routinely attract thousands of views — she wasn’t expecting to be one of just two trans women in a room of hundreds during orientation, or to have other students point out her gender identity in class.

“It was a surprise when I got here,” she said. “The plan was, ‘It’s a women’s college so they’re just going to assume female, and I’m going to pass like you wouldn’t even believe. I’m going to go there and no one’s going to know I’m trans’ — except I’m really bad at that. It’s clear that I’m not good at just blending in and passing. I have passions, and those come out.”

Those passions found an outlet in rejuvenating the years-dormant “Gender Splendor” club for trans and non-binary students. In April, seven club members sat in a circle on a grassy lawn at the center of the college, as other students played volleyball steps away. The members contemplated events they could plan in the fall, like an orientation-week panel on resources they’ve found helpful.

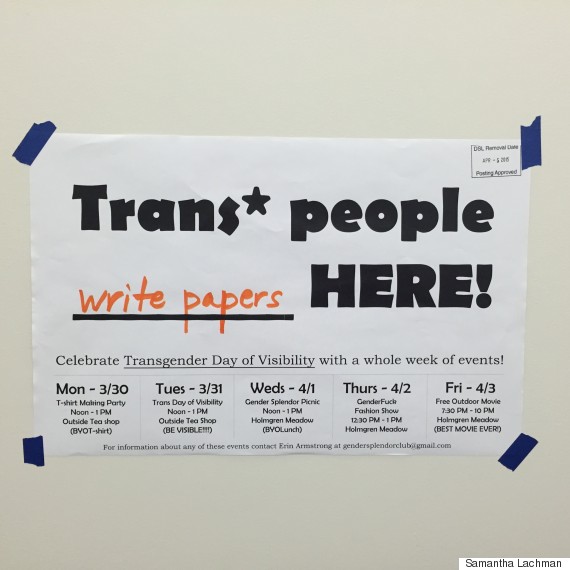

Armstrong has already made her mark at Mills. During Transgender Visibility Week, her club put up posters across campus that said “Trans people ___ here,” and had students fill in the blanks.

“When I was taking them down after the week was over, people were like, ‘No, don’t take them away!'” Armstrong said.

Students also decorated T-shirts on the first day of the week with messages about what gender meant to them. Armstrong’s read “f*** gender” in cheerful block letters.

As the debate continues about the purpose of women’s colleges and how transgender students fit in — a recent New York Times Magazine feature on Wellesley focused on trans men — Sonj Basha, a Mills student who identifies as genderqueer, said they were troubled that narratives about the policy changes have been masculine-centric.

“Mills has tried to really create the culture of not centering one voice within all of that,” Basha said. “[The policy] is not to perpetuate the privileges of cisgender men or of masculinity in general, but rather to allow people with diverse gender identities to have access to a woman’s college which can be a safe container, that maybe public universities or other places in which the binary is reinforced don’t offer.”

Basha said they hoped there could be more of an understanding of how gender intersects with race, class, disability, sexuality and other factors, as women’s colleges increasingly are understood as institutions that seek gender justice.

“My race has informed a lot of my gender; so has my class,” Basha said. “It’s important to recognize that gender is just one piece of who we are as individuals — if we confine even what gender justice is into one narrative, then that’s not actually justice.”

To that end, Basha sat on a panel in September with trans women activists CeCe Mcdonald and Miss Major to discuss the intersections of gender, race, class and violence. The transgender individuals who are most vulnerable to assault are those of color, as the panelists noted.

At Mills, Basha doesn’t fear for their life, an emotion they have experienced outside its boundaries.

“Mills has been a space where I can concentrate and focus on other things because [fear is] not an issue,” they said.

Sonj Basha, a Mills College senior, helped shape the school’s new admissions policy for transgender women and non-binary applicants. (Babak Gholamhossein)

Beyond providing the benefits of safety, the college’s first-in-the-nation distinction has had positive consequences for its profile among prospective students.

“Most of our increase in engagement has been an interest for whom the policy does not apply, for whom Mills was put on their radar by being a women’s college that was the first,” Vice President for Enrollment Management Brian O’Rourke told HuffPost.

But despite the momentum generated by the policy, and the new visibility non-binary and trans students carry on campus, crucial recognition factors like pronouns continue to be a struggle. The Mills media relations coordinator who sat in on HuffPost’s interviews unintentionally mis-pronouned two of the three students interviewed, and senior Skylar Crownover, who is a trans man and student government president, noted that he was frequently misgendered in his first two years at Mills because he was still being read as female.

At women’s colleges, the gender binary is gradually being left behind in favor of a more expansive understanding of self-identification and expression. What’s yet to be determined is whether the world beyond these schools will drag them toward that binary deconstruction, or whether they’ll beat them to it. Armstrong hopes these conversations about gender will one day become unnecessary.

“There is so much more to me than just my status as a women,” she said in a video posted to YouTube. “Look at me as a whole person. Maybe one day the novelty of trans people will wear off and we can just be people.”

Editor’s note: This story utilizes the pronouns preferred by the subjects involved, including she, he and they.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Source: Huffington Post Women